The European Union has strategically bet on Serbia's lithium deposits to support its ambitious transition to electric vehicles. Instead, however, it has faced dirty politics and powerful environmental resistance that has not only poisoned relations between Belgrade and Brussels, but also overshadowed the country's aspirations to join the Community, writes in an analysis "Politico"

The Jadar lithium deposit in Serbia is considered one of the richest in Europe - potentially enough to power the production of one million electric vehicles and cover up to a quarter of the continent's needs. This puts the mine at the centre of EU efforts to secure strategic resources needed for the transition to a fossil-fuel-free economy.

It is not surprising that the mining project, developed by global mining giant Rio Tinto, could receive key support from Brussels under the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which aims to reduce the EU’s dependence on China for supplies of vital resources.

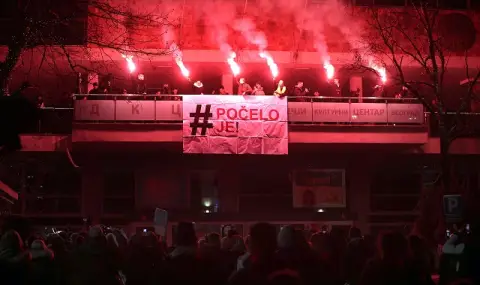

But fierce opposition from Serbian citizens – motivated by environmental concerns and accusations of corruption and clientelism by political elites – threatens not only the project but also overall support for European integration, which currently hovers around 40%.

"If the EU decides to stand behind Jadar, it will send a message that economic interests trump the Union’s core values – with potentially dramatic consequences for Serbia and the region," says Aleksandar Matkovic, a researcher and Belgrade-based organizer of the anti-mine protests.

The movement against the mine is already part of a broader wave of anti-government discontent in Serbia. Tensions have escalated further after the broadcast of a documentary made by a metallurgist who supports the project and controversially labels its opponents as "Russian agents".

This accusation was even made by the Wall Street Journal, while at the same time the activists were called agents of the EU and China. "We cannot be agents of three different world powers," said Matkovic of the Institute of Economic Sciences in Belgrade.

On March 25, European Commissioner for Industry Stefan Séjourne announced 47 strategic projects under the Critical Raw Materials Act, but surprisingly, not a single one of them was outside the EU territory — a decision that raised questions about whether the Jadar scandal played a role.

The Commission declined to comment on whether the Jadar controversy had influenced the list of projects, but stressed the importance of the strategic partnership with Serbia.

"This partnership in no way changes the EU's approach to the fundamental principles of the accession process," a Commission spokesperson said. "It has the potential to bring investments in raw materials, batteries and electric mobility that will boost economic growth, as well as the green and digital transitions, creating new jobs."

Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić met for dinner in Brussels with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa. The meeting was marked by sharp criticism of the deteriorating state of democracy in the country.

EU leaders made clear their dissatisfaction with the way Vucic has been handling the more than four-month-long student and mass demonstrations against his rule. Vucic, for his part, accused the protesters of being financed by Western powers - using the all-too-familiar refrain of "foreign interference" in Serbian politics.

"Serbia must implement the necessary reforms required by the EU - especially in the areas of media freedom, the fight against corruption and electoral reform," von der Leyen wrote in a post on social media after the meeting.

Now all eyes are on the next list of CRMA projects and whether Jadar will find a place in it.

Séjourne indicated that she would "present the selected projects in the coming weeks" and added that initiatives outside the EU "will not be wiped off the map".

If Jadar receives European support, it would facilitate access to funding - although without the advantages enjoyed by projects within the Union, such as accelerated approval procedures and direct financial assistance.

MEP Hildegard Bentele, a representative of the German Christian Democrats and a member of the European Commission's advisory panel, believes that the Jadar project is "of crucial importance for Serbia, for the EU and for the entire automotive industry".

But for many Serbs, Jadar now represents an alliance between the EU and a mining concern that has been built to the detriment of the public interest, with Germany’s industrial ambitions and the EU’s drive to catch up with China in electric vehicles taking precedence. At the same time, public distrust is growing — many believe that only politicians will benefit from the project. (Serbia has the lowest score among Western Balkan countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.)

"The real problem is corruption," says Marija Vuković, an environmental activist from Loznica, a town in western Serbia near the deposit. "People are afraid because they don’t trust the government."

In January 2022, The Serbian government officially suspended the project after mass protests, with citizens blocking roads and bridges in protest of the planned mine. However, Rio Tinto has retained its office in the country, acquired more than 500 properties in the area and claims to have already invested more than $500 million in the venture.

Last year, Vucic declared that "there will be no lithium mining without public support." At the same time, however, his government passed legislative changes that ease mining procedures - a sign that critics say is paving the way for a restart of the project.

"Nobody believes the project is completely stopped," says Vukovic. "Everyone here expects it to come back in some form — they are just waiting for the storm to pass."

The project has already divided the local community. Some residents - especially those who sold their land to Rio Tinto - support it, hoping for jobs and economic growth. But others fear serious environmental damage, including water pollution and loss of fertile land.

According to Vukovic, local farmers fear that the region will be turned into a "sacrifice zone" if the project goes ahead.

Rio Tinto insists that it complies with all environmental and social standards, and is willing to work in partnership with local communities. The company hopes the project will be put back on the agenda, especially in light of the new strategic partnership between Serbia and the EU in the field of raw materials.

For Brussels, the dilemma is clear: can the EU support a project with such serious strategic value for the electric vehicle industry - without being associated with an unpopular leader, a controversial project and potential environmental damage?

Geopolitical tensions in the Balkans are also not abating. Serbia maintains close ties with Russia and China, and despite being in negotiations for EU membership, it often maneuvers between different foreign policy directions. Support for Jadar could reinforce the country's Western orientation - but it also risks exacerbating domestic political instability.

"The EU cannot afford to appear to be supporting authoritarian leaders in exchange for raw materials," says Matkovic. "This undermines the very foundations of the European project."