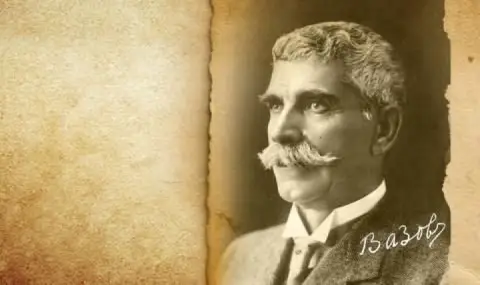

On September 20, 1916, Ivan Vazov's candidacy for the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1917 was nominated. On this date, 108 years ago, Prof. Ivan Shishmanov and the chairman of the National Academy of Sciences Ivan Evstatiev Geshov nominated Vazov for the Nobel Prize for Literature. The writer is already popular in Sweden – in 1895 his novel “Under the Yoke” has been translated there.

This recalls on "Facebook" Tihomir Ilchev.

The Swedish translator is Dr. Alfred Jensen. In 1912, he was already a member of the Nobel Committee, which sent him to Bulgaria with the mission of meeting Bulgarian scientists and writers.

In his memoirs, the writer's friend Ivan Shishmanov wrote that when Jensen was in Bulgaria, the people from the “Misl“ they spoke to him against Vazov. Pencho Slaveykov himself never hid his ambition to also achieve the distinction. It is believed that this opposition along the “old – young“ may have influenced the committee's final decision.

Jensen was Vazov's translator, but also a close friend of Pencho Slaveikov. That is why the Swede asked to propose Slaveykov for the prestigious award.

„The Swedish Academy is in the fortunate and quite extraordinary circumstances of being able to present to Europe an indisputably great poet, in whom the presence of a poetic masterpiece can be ascertained – “Bloody Song”.

This is part of Alfred Jensen's text nominating Pencho Slaveikov for the European literary award. The date is January 30, 1912, and the Nobel Prize has not yet established itself as a world prize.

Jensen has long been known both in Sweden and Bulgaria. Already at the end of the 19th century, he traveled around the Balkans and wrote sketches and travel notes about them – mostly for Slavic countries. He visited Ruse, found Sofia to be modern, where he also met Vazov, Yavorov, P. Yu. Todorov. In 1891, he published an essay about Botev under the title "Hristo Botev. Bulgarian poet of freedom”, containing translated poems and memories of Botev's contemporaries. In 1893, he began to translate “Under the Yoke”. Sam Jensen is a poet, but he is also a translator, journalist, specialist in Slavic literatures, and as an expert on them he was elected a member of the Nobel Committee. This gives him the right to nominate a Nobel candidate on his own behalf.

The nomination is supported by an extensive motivation, in which, along with “Bloody Song” Slaveykov's work is examined. As is known, Jensen separately translated and published in 1912 two collections of poems by the Bulgarian poet, entitled “Koledari” and “Destinies of Poets”, which he subsequently applied to his proposal (it was presented in its entirety in April 1912). The Bulgarian poet attracts him with the wide culture and diverse themes of his work, but “Bloody Song” is the representative work with which he concretizes his motive for the nomination of Slaveikov.

But “Bloody Song”, on the other hand, is unfinished, and disturbing plots are playing out around its creator, which do not remain hidden from the Swedish scientist. He did not receive a written confirmation offer from the Bulgarian cultural institutions, although one was promised by Sofia University. At the same time, separate institutional actions were carried out to nominate another Bulgarian writer, at the same time possessing the no less modest role of an epic – Ivan Vazov.

Even the year before, his friend Ivan Evstatiev Geshov suggested to Jensen to nominate the author of “Under the Yoke” for the Nobel Prize. Later, in a letter dated December 13, 1911, Ivan Peev-Plachkov – secretary of the Bulgarian Academy Literary Society, which was renamed the previous year, informs Prof. Ivan Shishmanov that “a lot has already been done” regarding the nomination. In the “Nobel” Library all Vase works were sent according to the regulation of the Nobel Committee. The question of the Bulgarian nomination has already been discussed in the Management Board, and Ivan Shishmanov was unanimously chosen for its formal implementation.

In his short answer, however, the professor – although “Vazova's name is dear to me” – comes out with an opinion “that nothing should be done before we are absolutely sure that our proposal will be taken into consideration”. It is obvious that Ivan Shishmanov wants to know in advance Vazov's chance of receiving the Nobel Prize. He directs a direct and anticipatory question to Jensen: “Is there any prospect of Vazov receiving the literary prize for 1912?”.

For his part, Jensen seems to have long pursued an exploratory policy through his correspondence with the Academy and with Slaveykov. It can be assumed that the strange approach of the Bulgarians to the nomination, based on mutual silence between the candidate lobbies, did not escape the Swedish scientist. There is serious institutional support for Vazov, while there is none for Slaveikov.

It is clear from all the published documents that Jensen had previously focused on Pencho Slaveykov, whose works he had already personally translated, but without neglecting the free choice of the Bulgarian side. In a letter to Ivan Geshov, he explicitly reminds that “requests regarding candidacy for the Nobel Prize must be submitted before February 1 to the secretary of the Swedish Academy, Dr. C. D. of Vissen”.

However, such a request was not received either by Vazov, despite the Academy's actions, or by Slaveykov, despite the University's promise. Therefore, on January 30 – two days before the deadline – Jensen took advantage of his right to personally nominate Pencho Slaveikov for the Nobel Prize. An additional reason for this decision is probably the fact that contacts with him are not marked by the officiality that accompanies contacts with Vazov regardless of the personal acquaintance of the two.

Did the author of “Bloody Song” ever hoped for this nomination, it cannot be said with absolute certainty, while in a separate note Shishmanov notes that “Vazova's dream for years was to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature (even before the death of Pencha Slaveikova)” .

Later, the professor tried to rehabilitate himself for his vacillating attitude towards Vazov's candidacy, interceding personally with Jensen with a proposal letter in which he emphasized Vazov's importance as a popular writer. In this sense, the existing opinions that Shishmanov's preliminary question whether there is a possibility that Vazov will receive the “Nobel Prize for 1912” is an attempt at a direct “breakthrough” are groundless.

Slaveykov's death, however, foils Jensen's personal intention anyway.

Unfortunately, in 1917 the prize was not awarded to Ivan Vazov, but to Werner von Heidenstam (Sweden).

Until now, the candidates for the Nobel Prize for Literature in our country have been Ivan Vazov, Pencho Slaveykov, Elisaveta Bagryana, Emilian Stanev, Lyubomir Levchev, Blaga Dimitrova, Yordan Radichkov.