We present the analysis of Tanisha Fazal, a professor of political science at the University of Minnesota and author of "The Death of the State: The Politics and Geography of Conquest, Occupation, and Annexation".

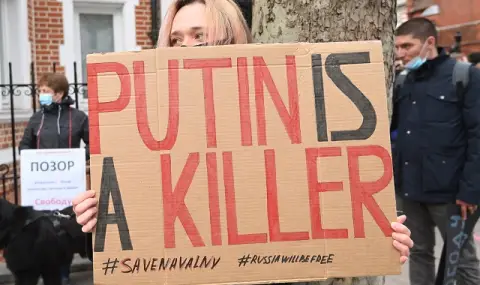

The norm against territorial conquest has been a pillar of the international order since 1945, but that pillar is now crumbling. Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is surely the most egregious recent violation of this prohibition—extraordinarily, as an attempt to conquer an entire sovereign state. Yet if Moscow were to walk away with parts of Ukrainian territory, and especially if that transfer were to gain international recognition, other powers might be even more tempted to wage wars of conquest.

States have never consistently observed the rule, enshrined in the UN Charter in response to Nazi Germany’s takeover of other countries during World War II, that prohibits the forcible seizure of another state’s territory. But it was widely observed until very recently. Argentina was quickly ejected from the Falkland Islands after its 1982 invasion by the combined forces of the British military and a UN Security Council resolution. After Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, a US-led, UN-approved coalition intervened to restore Kuwait’s sovereignty. When Russia invaded Crimea in 2014, however, outside powers were unable to fully enforce the norm. Many countries protested, but Crimea’s transition to Russia became a de facto reality. And this time, after Russia’s full-scale invasion, the world’s increasingly mixed response to such a blatant assault clearly signals the humiliating weakness of that norm.

Normals are dying slowly. Attempts at land grabs as large and brazen as Russia’s in 2022 are likely to remain rare, at least for now. But as aggressors go more or less unpunished, states may increasingly act on territorial claims in unclear jurisdictions—those least likely to provoke a significant international response. These small-scale attacks may prove most damaging to the norm against territorial conquest. As violence escalates, the larger web of rules and institutions that make up the international system may begin to unravel. Although far from inevitable, the death of the norm will leave the world in perilous waters.

How healthy is the international norm?

The health of a norm in international relations can be judged by the actions and statements of the countries responding to the violation. Immediately after Russia’s invasion in February 2022, many countries came out in defense of the ban on territorial conquest. But that outrage has become more muted in the years since. Although the European Union, the United States, and their allies have imposed strong and consistent sanctions on Russia, many countries maintain normal relations with Moscow. Under the Trump administration, Washington’s continued participation in the sanctions regime is already in question.

The court of global public opinion on Russia’s war in Ukraine is increasingly divided. The European public generally supports Ukraine’s resistance to Russian invasion—the fear that Russia might turn on other European countries gives them a clear interest in maintaining the norm against territorial conquest. But even in Europe, support for fighting until Ukraine’s losses are fully recovered may be waning. And in the United States, where President Donald Trump has signaled that he is less committed to Ukraine’s survival than his predecessor, Joe Biden, concerns about Ukraine in particular and the preservation of the norm of sovereignty in general are not as prominent as in Europe. Recent polls show growing support, especially among Republicans, for ending the war in Ukraine, even if it means Ukraine having to cede territory to Russia.

Many outside the West were horrified by the Russian invasion in 2022. Martin Kimani, Kenya’s then ambassador to the United Nations, spoke at a UN Security Council session a few days before Russia’s invasion in February 2022 and condemned “irredentism and expansionism” and the withering of international norms “under the relentless assault of the powerful.” But many commentators in the global South have also criticized Europe and the United States for taking a selective approach to enforcing norms; many Western states that opposed Russia’s attack on Ukraine have themselves violated state sovereignty in the not-so-distant past, such as the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, or have condoned other violations of international law, such as their support for Israel’s war in Gaza. Inconsistent responses to various violations of sovereignty beyond the mere seizure of territory can undermine all of these interconnected norms. After all, norms lose their force when they fail to prevent powerful states from doing what they want.

Still, the fact that states feel obligated to invoke the norm against seizure of territory, even when they violate it, shows that there is still life in the norm. Russian President Vladimir Putin has argued that Ukraine is not a real state, which would mean that the ban would not apply. Beijing similarly argues that Taiwan has always been part of China, and Israel does not recognize Palestinian statehood. Rwandan President Paul Kagame has used the M23 rebel group as a front to launch territorial incursions into the Democratic Republic of Congo, while insisting that Rwanda is not involved in the conflict and that its interests are purely defensive.

Venezuela’s 2023 referendum to seize the territory of Guyana invoked decades-old international agreements to support its claim, while ignoring other, more recent, International Court of Justice rulings that rejected it. Even Trump’s statements that the United States will buy Greenland, renegotiate rights to the Panama Canal, take over Gaza for development, and make Canada the 51st state seem to favor transactional agreements over coercion. But Trump’s refusal to rule out the use of force and the United States’ refusal to name Russia as the aggressor in Ukraine in a recent G7 resolution and a UN vote are worrying steps in the wrong direction. If and when states stop invoking the norm against territorial conquest or rationalizing their actions in ways that show weak support for it, the norm will die. Bolder and more frequent territorial aggressions may follow.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

Bite-sized states may be more damaging to the norm against territorial conquest than attempts to swallow it whole. Let’s compare the global response to Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 with the response to its full-scale attack in 2022. Both clearly violate the norm. In 2014 The world’s response was relatively weak: the seizure was condemned in principle, but there was little material resistance to Russia beyond sanctions, and even today few expect an agreement to return Crimea to Ukraine. By normalizing limited, if still brazen, territorial gains, the half-hearted response may have paved the way for Moscow to invade in 2022. In this case, the world reacted more strongly precisely because Russia’s claims extend to an entire country—a clear, undeniable violation of the norm. Now consider a comparative scenario in which Russia attacks only the Donbas region of Ukraine in 2022. The outcome in terms of territorial control may not be much different from the likely outcome of a full-scale war, with Russia taking Donbas and Ukraine surviving on a reduced scale. But a smaller-scale land grab by Moscow would probably not have provoked such a vigorous international response. If norms are as strong as the world’s reaction to their violation, a more limited Russian invasion would set the norm against conquest on a more certain, if slower, erosion path.

However, any transfer of Ukrainian territory to Russia would further normalize territorial conquest. The damage could be minimized if the transfer were unofficial, with a frozen conflict giving eastern Ukraine a status similar to that of Abkhazia and South Ossetia—territories that Russia controls but that most of the world considers part of Georgia. Equally likely, however, is a transfer of territory that comes with at least some international recognition. An agreement between the United States and Russia that leaves Ukraine out, or even a European-brokered truce that includes a promise of security guarantees for what remains of an independent Ukraine, could effectively legitimize the partition of Ukrainian territory. The forcible transfer of territory would not only be legalized, but would also occur with the approval of the United States, one of the historical guardians of the norm.

The outcome of a war will not decide the fate of the norm, and a full-scale revival of territorial conquest will not happen overnight. In other words, states are unlikely to suddenly start making claims as bold as Russia’s in Ukraine. But as the international environment becomes more favorable to territorial claims, revisionist states may test the limits with smaller-scale aggressions against weaker targets. Azerbaijan’s takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023, which provoked minimal global response, is a recent example. Sudan could then seize Ethiopia’s Amhara region. China could take a more aggressive stance in the South China and East China Seas. Venezuela already claims large parts of Guyana and could act more forcefully on those claims. The Palestinian territories, Taiwan, Western Sahara, and other states not widely recognized as sovereign states would be particularly vulnerable. Even more worrying is the possibility of escalating border conflicts between nuclear-armed states such as China, India, and Pakistan.

As aggressors go unpunished, states may increasingly act on the basis of territorial claims.

Looking ahead, if the norm against conquest continues to erode and countries no longer fear serious reprisals for territorial aggression, threats that now seem distant or exaggerated may become real possibilities. Buffer states—geographically situated between rival countries—will be particularly vulnerable to attack. In the mid-twentieth century, Poland was trampled and dismembered by wars between larger powers. Today, other former Soviet satellites or former republics of the USSR, caught between NATO and an increasingly revanchist Russia, may face a fate similar to that of Ukraine. If Sino-Russian relations deteriorate, Mongolia could also be at risk, as neither of its more powerful neighbors would have any assurances that the other would not act first to take over the state that divides them. Nepal and Bhutan are also in precarious positions between China and India. Kuwait could again be in danger, as it sits between regional rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Related norms could also begin to weaken. If territorial conquest returns to the table, states will be less willing to respect other elements of sovereignty, such as maritime rights. When small island states claim fishing and mining rights in exclusive economic zones, other countries in the region may simply ignore their claims. Normative law could be disregarded. Violations of political sovereignty—from election interference to regime change—could become not only more frequent but also more overt. Such violations have always occurred, but norms have somewhat limited them and provided some protection for weaker states. If the strong no longer follow the rules, they undermine social constraints on acts of violence against institutions, land, and people.

The erosion of the norm against territorial conquest could even precipitate a broader shift in an international system built on relations between sovereign states. Several challenges to sovereignty are already emerging, such as the threat posed by climate change to small island nations, or the way in which technology companies have taken over communications, diplomatic, and military roles once reserved for governments. The return of the ability to conquer territory would increase these pressures. If the survival of a state threatened by an aggressor is increasingly in doubt, that state’s ability to negotiate security and economic agreements will also diminish. And if state sovereignty becomes generally insecure, it is unclear how the open markets that underpin the global order will function. Moreover, conquest is fundamentally incompatible with democracy. Many principles of the liberal international order cannot survive in the absence of a norm against territorial conquest. Perhaps that is the goal.

A steady decline

The norm against territorial conquest has been the foundation of U.S. power for the past eight decades, stabilizing the international system and allowing the United States to build a network of enduring alliances and to prosper from trade that is largely unscathed by conflict. But it has not served all countries equally well. The norm itself rests on troubling foundations—its strongest supporters imposed rules on the rest of the world after centuries of colonialism in which they redrawn borders at will, and in the decades since have repeatedly flouted their own rules and violated the sovereignty of weaker states. Weaker states have also suffered the most from the perverse incentives the norm creates. Knowing that their borders are largely secure, the greedy leaders of such countries can direct resources toward internal security and repression while plundering state coffers, creating the conditions for instability, civil war, and state failure.

Yet the norm against territorial conquest has suppressed the brutality that accompanies wars of annexation. As political scientist Alexander Downs has shown, armies deployed to seize territory often target civilians as well. The brutality of Russian forces in Ukraine and the deportations carried out by Azerbaijani forces in Nagorno-Karabakh are just the most recent examples. Conquest can involve ethnic cleansing, as illustrated by the recent U.S.-backed Israeli proposal to empty the Gaza Strip and relocate its population to nearby countries. At a fundamental level, conquest ignores the will of the local population; Western Guiana does not want to be part of Venezuela, any more than Ukrainians want to join Russia.

Norms lose their power when they do not prevent powerful states from doing what they want.

The steady decline of the norm—and the disruption that could follow its demise—is not a foregone conclusion. A more transactional understanding of territory, like Trump’s proposals for the United States to purchase Greenland, develop Gaza, and renegotiate rights to the Panama Canal, is unlikely to replace it. People’s attachment to their homeland and the pull of forces like nationalism are too strong, and pursuing deals that ignore both could provoke a large-scale, violent pushback.

Even if the United States were to abdicate its traditional role of enforcing order, other key powers that benefit from the relative peace that the norm allows could intervene. China, for example, has built its power within the institutional architecture of the postwar international order and has always been fiercely protective of its own sovereignty. It is possible that China could follow the example of the United States and chart a similar trajectory of territorial expansion followed by global leadership. Beijing could first exploit the relative weakness of the norm to satisfy its territorial ambitions, by absorbing Taiwan and cementing its island and maritime claims in the South China and East China Seas. But it could then try to impose some constraints on conquest—still allowing limited intervention in other countries but threatening economic or military retaliation against those who engage in territorial aggression, especially in China’s own region, to prevent unrest that would undermine its economic and security interests. Such behavior would be hypocritical, but sovereignty norms have always been violated hypocritically; an example of this is the repeated foreign interventions by the United States, long the foremost defender of these norms.

Yet any move toward a watered-down or distorted version of the current norm against territorial conquest would lead to an increase in land conflicts. Since World War II, many countries have grown accustomed to and benefited greatly from the relative stability of the US-led order and the respect for territorial sovereignty it imposes. It is difficult to say how far the system might unravel if current constraints on territorial conquest continue to be relaxed. But both weak and strong states will surely regret the norm when it disappears.